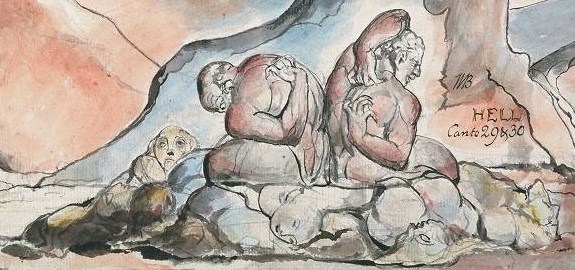

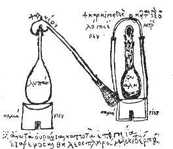

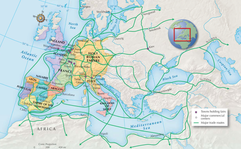

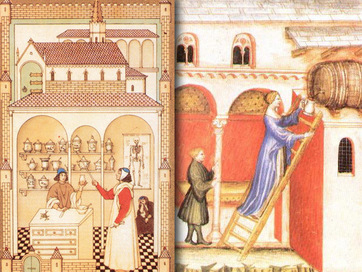

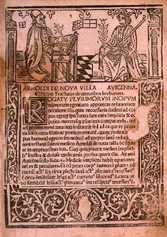

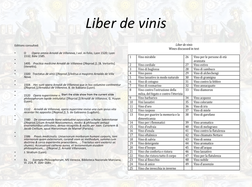

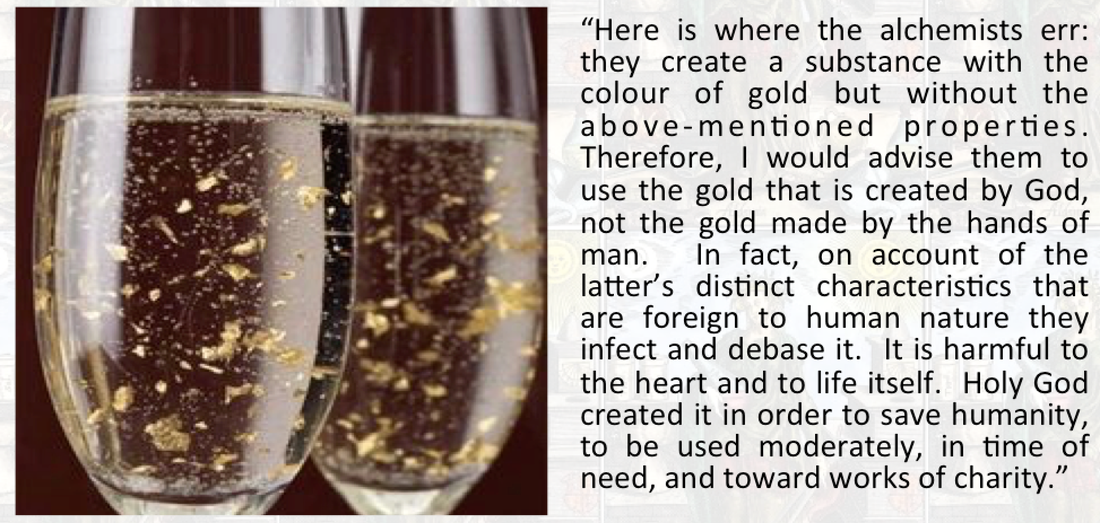

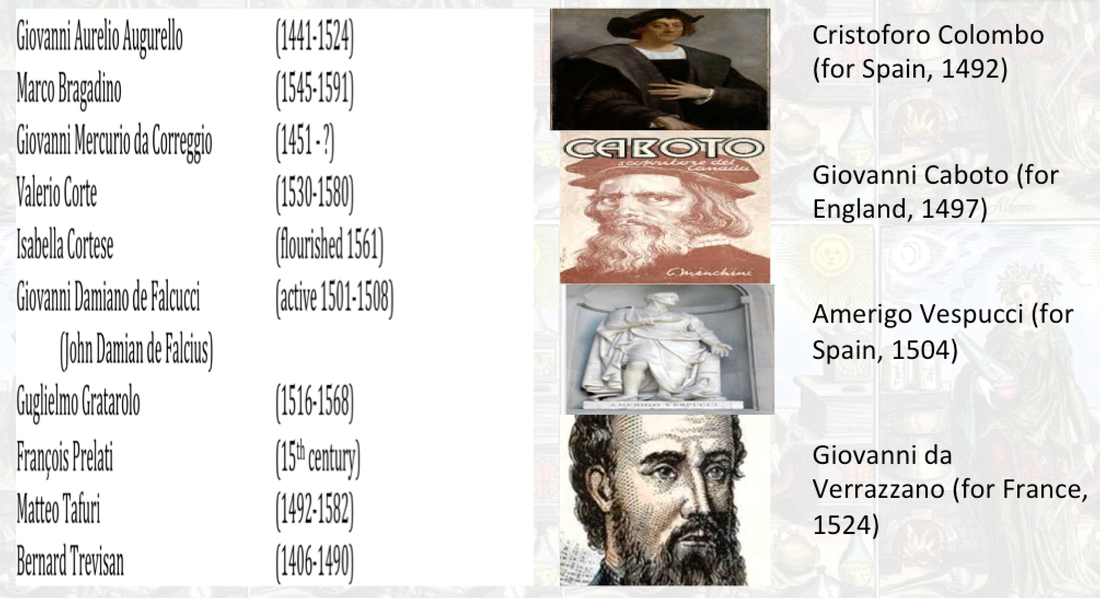

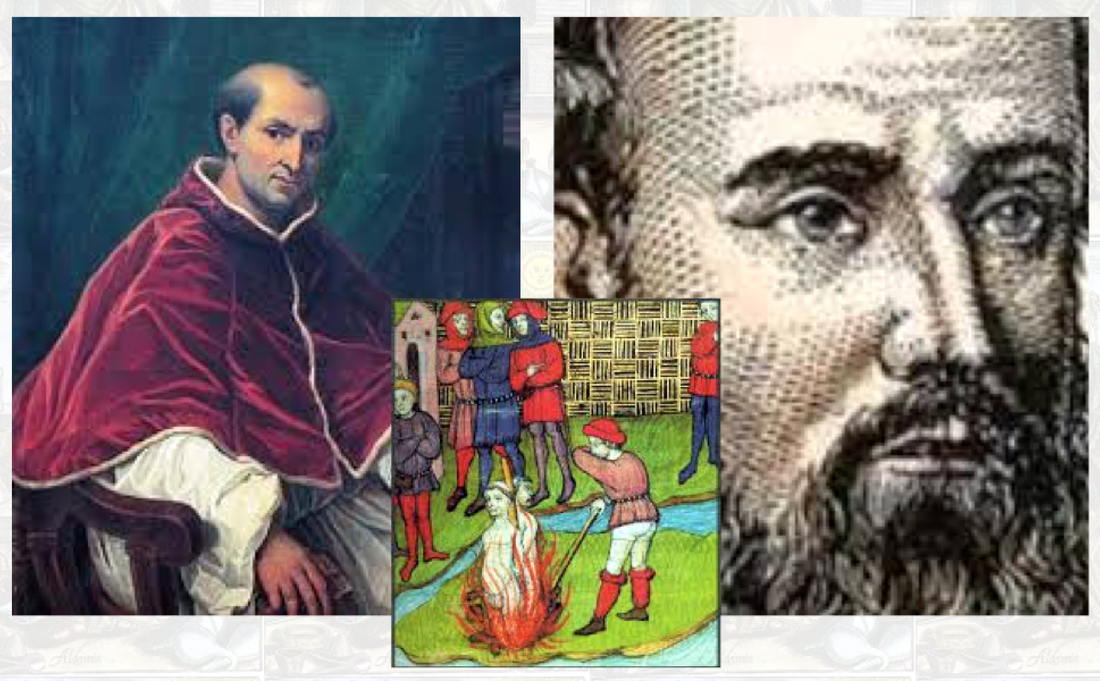

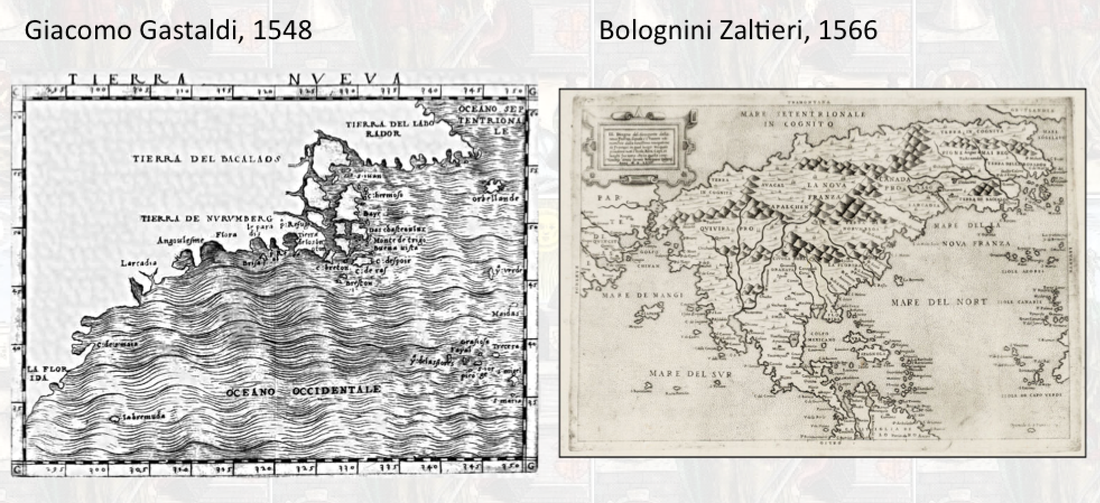

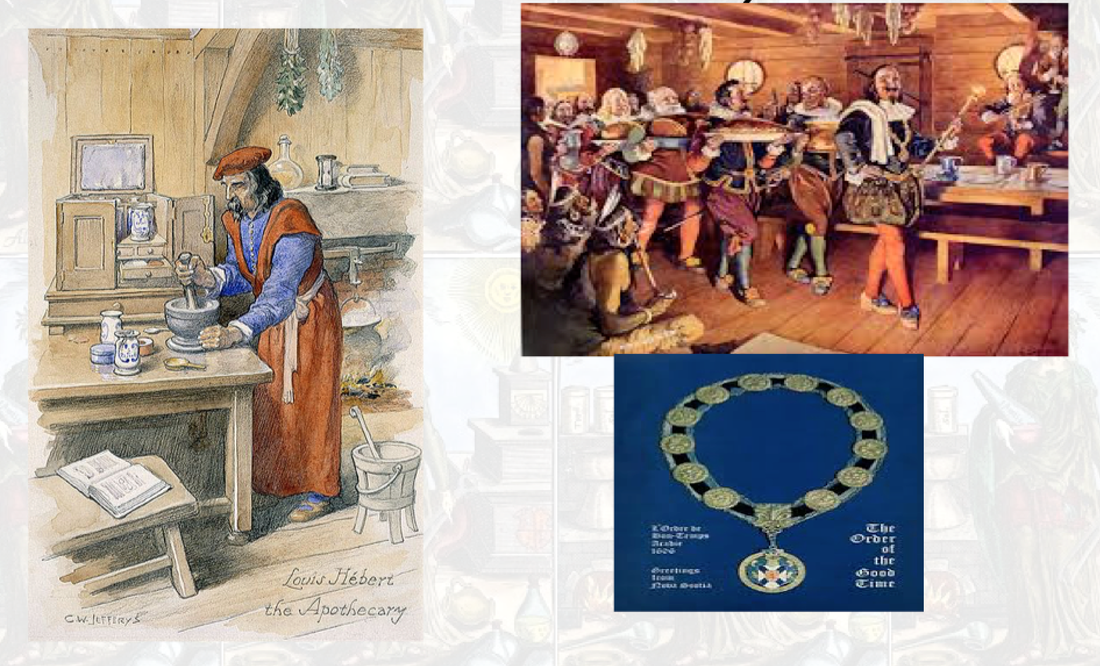

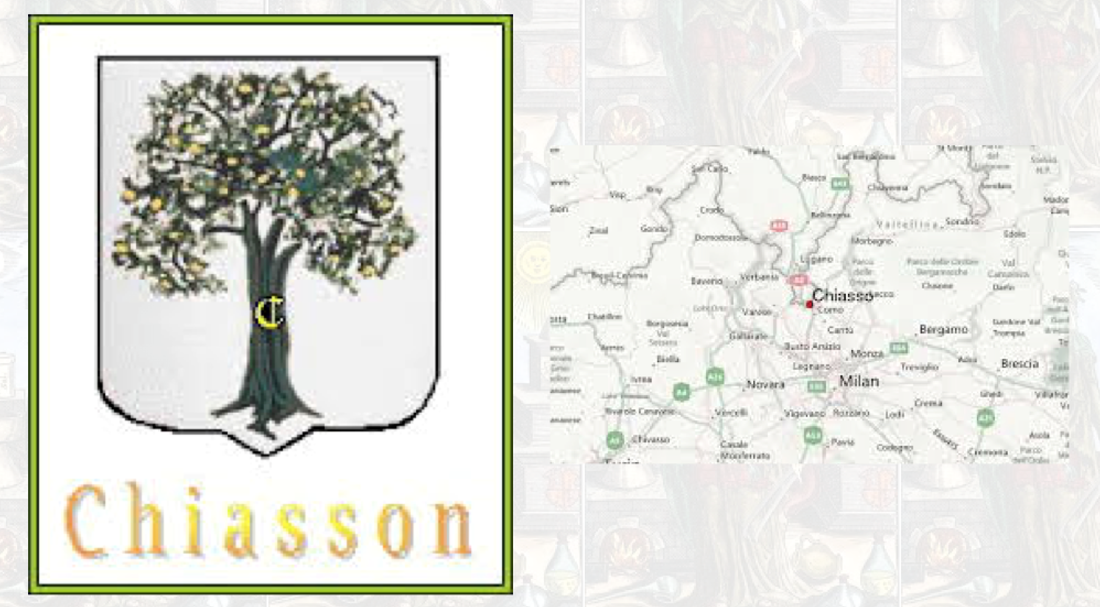

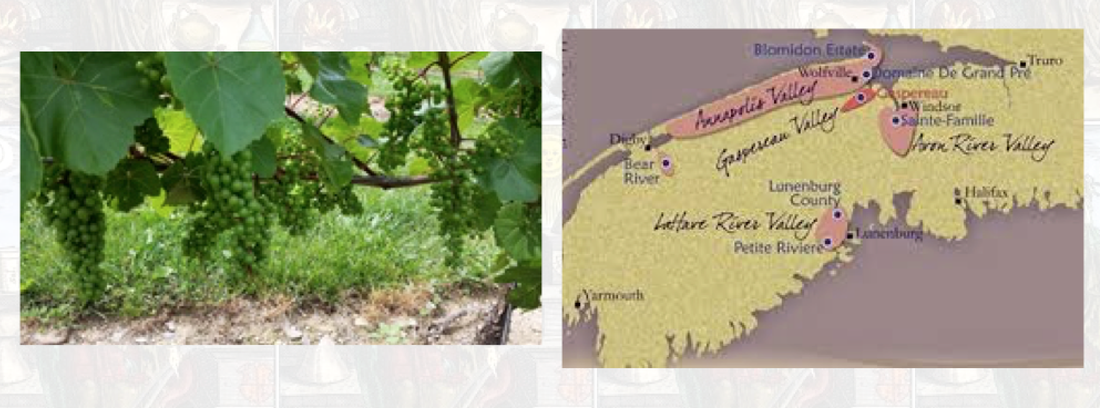

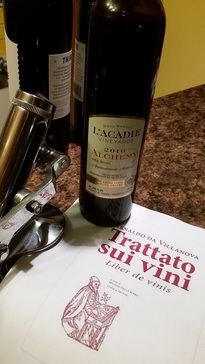

While many people have heard the term ‘alchemy’ bandied about in different contexts, few have probably looked into the etymology of the term and the origins of the practice. Still fewer make the association between wine and alchemy's search for the "elixir of life" ... yet, there is a connection. What's more, there is one to be made right here in Nova Scotia. As with all mysteries, it is for the initiated ... . Frequently, the more negative aspects are among the first associations. For example, synonyms for the word alchemy often include such terms as witchcraft, magic (also black magic), pseudo-science, even sophistry, chicanery and charlatanry. In canto 29 of the Inferno, Dante places the alchemists in Circle VIII, Bolgia X with the falsifiers of metals, persons, coins and words. The souls are heaped on the ground or crawling around, suffering from horrible illnesses. They are covered in scabs, scratching themselves violently because they suffer from a terrible, unending itch. Dante compares their scratching to someone scraping the scales off a fish with a knife.  The reason for this punishment is that, according to contrapasso (the process by which a sinner receives a punishment that either resembles or contrasts with the sin itself), since the Alchemists corrupted God's creations through their art, their punishment is for their bodies to be corrupted into putrid, rotting hunks of flesh. The decomposition of flesh may also allude to the long-term effects that Alchemists would probably have experienced. If, for example, one is working extensively with lead trying to turn it into gold, one may easily develop lesions that could become rather disgusting infections. An Alchemist's experiments dealt with many caustic and/or carcinogenic elements like mercury, sulphur, etc.  It is entirely possible that an alchemist would have looked like the 'before' pictures on a ProActive commercial. Dante is taking that image to the extreme. One would have seen the illness suffered by alchemists as a divine punishment in life. With Dante, it is carried over to eternity.  "But Minos to this chasm, last of the ten, For that I practised alchemy on earth, Has doom’d me. Him no subterfuge eludes. " (Grifolino) "So shalt thou see I am Capocchio’s ghost, Who forged transmuted metals by the power Of alchemy; and if I scan thee right, Thou needs must well remember how I aped Creative nature by my subtle art." (Capocchio) The punished alchemists in Dante’s Inferno are identified as Grifolino d’Arezzo and Capocchio of Siena. The former promised to teach the Bishop of Siena to fly. When he could not (after accepting payment, of course), the Bishop had him burned at the stake. The latter created credible imitations of precious metals. Both of these souls are actually Sienese, by the way. As we know, the roots of the negative connotations are in the claims of transmutation, from lower (or baser) components to higher, more elevated ones. In particular, this would refer to the common assumption that all alchemists attempt to turn base metals into gold. However, alchemy is much more than simply changing lead into gold. In her book Alchemy, historian Cherry Gilchrist makes this important point: "Mainstream alchemy is a discipline involving physical, psychological, and spiritual work, and if any one of these elements is taken out of context and said to represent the alchemical tradition, then the wholeness and true quality of alchemy is lost."  The decidedly psychological aspect of alchemy that is inspired by Carl Gustav Jung’s Alchemical Studies (first published in 1967 but traced back to his interest in the subject since 1929) makes a fundamental point concerning the concept of transmutation. If the Alchemists hope to achieve the Lapis Philosophorum (Philosopher’s Stone) through which they can redeem base, vulgar metals, then they too must become redeemer figures. Since they were trying to redeem nature as Christ had redeemed man, there was an identification of the Philosopher’s Stone with Christ the Redeemer. From this perspective, the work of alchemy becomes a symbolic account of the fundamental process the human psyche undergoes as it tries to make meaning out of chaos. Just as the base metal is to become gold, the development from the blackness (nigredo) of nihilistic loss of value to the gold of the reconciliation of apparently irreconcilable opposites achieves higher levels of consciousness.  With reference to the work of the famous 16th-century physician and alchemist Paracelsus, Jung writes: [the wise man] “extracts everything meaningful and valuable as in a process of distillation and catches the precious drops of liquor Sophiae in the ready beaker of his soul, where they ‘open a window’ for his understanding. Paracelsus is here alluding to a discriminative process of critical judgment which separates the chaff from the wheat – an indispensible part of any rapprochement with the unconscious. It requires no art to become stupid; the whole art lies in extracting wisdom from stupidity. Stupidity is the mother of the wise, but cleverness never. The ‘fixation’ refers alchemically to the lapis but psychologically to the consolidation of feeling. The distillate must be fixed and held fast, must become a firm conviction and a permanent content.” Here, Jung refers to other very important aspects of alchemy that are of direct relevance tonight: distillation, the pursuit of the “liquor of wisdom” that lead to the elixir of life, a potion that grants the drinker eternal life, and/or eternal youth through still greater understanding. The origins of these meanings may be traced to the etymology of alchemy itself. Our “alchemy” and “alchimia” comes from Medieval Latin “alkimia” which, itself, is traced from Arabic “al-kimiya”, derived Greek “khemeioa” which could derive from and old name for Egypt, “Khemia” (land of black earth), or from the Greek “khymatos” (“that which is poured out”) from “khein” (“to pour”), related to “khymos”, meaning juice or sap. It appears to be associated with ancient pharmaceutical chemistry through the study of the juices or infusions of plants. The “Al” that precedes “kimiya” is the Arabic definite article, “the”. It is from the Egyptian city of Alexandria, a major centre of Hellenistic learning from ca. 331 BCE to 641 CE, that much scientific learning of the Middle Ages flowed. Across North Africa, through Muslim Spain, many classical texts that were otherwise lost during the European Dark Ages found their way back to Europe over the next few centuries. This is particularly the case with the Twelfth-Century Renaissance. During this period there was increased contact with the Islamic world in Spain and Sicily. This is also the period of the Crusades and the height of the Reconquista. Equally, contact with Byzantium, to many the Eastern continuation of the Western Roman Empire, was also greater. This allowed Europeans to seek and translate works of Hellenic and Islamic philosophers and scientists, especially the works of Aristotle. Consequently, this was the period of the development of the medieval universities that aided materially in the translation and propagation of these texts within a new infrastructure for scientific and intellectual communities. Our modern chemistry has etymological and scientific roots in the alchemical texts of the Middle Ages. In fact, for the Middle Ages and much of the Early Modern period, alchemy was chemistry. As one can see from the previous image of the trade routes, Italy was very strategically placed during this period, being very much at the crossroads of numerous cultures and traditions. In fact, Italy may claim one of the very first western European alchemists, Pietro Barliario (ca. 1055) who, as legend has it, may have constructed the famous acqueduct of Salerno with the help of the demons he conjured. Another legend has it that a Latin, a Greek, a Jew and an Arab met under the aqueduct while seeking refuge from a terrible storm. The Greek, Pontus, met up with the Latin Salernus who was injured. These two were later joined by a Jewish traveller named Helinus and an Arab by the name of Abdela. As it turned out that all four were practicing doctors of medicine, they chose to found a school of medicine in that very spot and to pool their intellectual resources in the pursuit of medical knowledge. Together, the two legends underline the association of medical and scientific learning in Italy with contacts between the same Hellenic and Arab world that brought us alchemy. The Scola Medica Salernitana and European alchemical studies in southern Italy and Sicily have some common points of contact. All the elements for a good alchemist joke here: a Latin, a Greek, a Jew and an Arab alchemist walk under an acqueduct … . I do have one alchemist joke to share:  Q: How many alchemists does it take to change a lightbulb? A: None. It is impossible. They keep transmutating the bulb filament into gold. It should come as no surprise, then, that an important treatise on alchemy and wine was another of the many results of these fascinating points of contact between cultures, traditions, knowledge in Spain and Southern Italy. Lest we forget, the ancient Greeks named southern Italy Oenotria on the basis of the many vines that grow there and from which one makes excellent wine, even to this day. One of the first texts to explicitly discuss the intellectual, medical, and scientific relationship between alchemy and wine was written by Arnaldo da Villanova. This eminent figure. also known as Arnaldus Villanovus, Arnaldus de Villa Nova, Arnau de Vilanova, Arnaud de Ville-Neuve, or Arnaldo de Villanueva, was a physician and religious reformer who also had a reputation for being an alchemist and astrologer. He lived from approximately 1240 to 1311. His place of birth is debated but almost for certain, he was born in a town or village with the name Villanova or Ville-neuve in either Montpellier, Languedoc, Catalonia or Provence. He wrote many works in the Catalan language in addition to Latin. He is credited with translating a number of medical texts from Arabic, for example, by Avicenna and Galen by 1260. In fact, he is almost certainly behind the papal bull of 8 September 1309, which required of medical students knowledge of some fifteen Greco-Arabic treatises, including those by Galen and Avicenna. He is the reputed author of such important medical works as Speculum medicinae and Regimen sanitatis ad regem Aragonum, and Breviarium Practicae. He is also credited with many alchemical writings, including the Rosarius Philosophorum, Novum Lumen, and Flos Florum. He also wrote many theological works for the reformation of Christianity in both Latin and his native Catalan, some of them including apocalyptical prophecies. He studied medicine in Montpellier until 1260 and he undertook studies in theology. He wandered France, Catalonia, and Italy, as part doctor, part ambassador. He was the personal doctor of the King of Aragon from 1281. At the death of Peter III of Aragon in 1285, he left Barcelona for Montpellier. Influenced by the Calabrian theologian Gioacchino da Fiore, in 1288 he wrote De adventu antichristi that prophesied the world would end in 1378 and the antichrist would come. He was Master of the School of Medicine in Paris from 1291 to 1299 when he was accused of heresy and imprisoned for his ideas on church reform. He was saved thanks to the intervention of Pope Boniface VIII whom he had cured of gallstones through the application of a gold astrological seal, according to legend. His fame was so immense that he counted three popes and three kings as his patients. We was also ambassador for King James II, King of Aragon and Sicily. He sought refuge from the Inquisition at the court of Frederick III in Sicily, and was later called to Avignon as doctor for pope Clement V. It appears he died in a shipwreck off Genoa in 1311 on his way to complete his mission to Clement V. Arnaldo da Villanova’s Liber de vinis was composed sometime in the early 1300s but most editions of his works, including the one from which this current one is drawn, appear from the late 15th to the late 16th centuries. Among the works consulted for the 2015 translation and reprint edited by Manlio Della Serra for Armillaria of Ciampino (Rome) are indicated above. The text itself offers recipes for 49 different kinds of wine and is very explicit in the health benefits of each. In fact, the focus of the treatise is to highlight those benefits in order to establish a harmony between the external and internal, improve one’s health and extend one’s life. These wines are very frequently a mixture of grapes with other fruits, vegetables and plants. In terms of making wine, Arnaldo insists that the container for the fermentation of the grapes be of good wood (at one point in the text, he remarks that cedar is recommended), free of any irregularities and unwanted odours. The must needs to be made from mature wines that, however, have not deteriorated in any way and/or are well on their way to becoming vinegar. He also points to three different techniques: The first is to boil the ingredients (particular fruits, vegetables, plants) with some of the must and then to remove the foam or froth. This mixture must sit for approximately 24 hours before it is filtered through white linen cloth. Then, it is blended with other wine must, placed in a barrel and covered, sealed and allowed to ferment. The cask is then closed and the wine rests (“riposerà”) until it is ready. No time referent is given here. He considers this technique the best. The second is to use fresh or dried ingredients (particular fruits, vegetables, plants), or, in the worst-case scenario, ground and placed in a linen sack which is then placed with the white wine must. These are then set to boil together until evaporated, then mixed with the base wine until it is made clear(er). It is to be used as needed. The third method consists in the use of fire (therefore, more boiling) and can be drunk pure, mixed with other wines, or even with water. Since the health of the drinker/patient is of paramount interest, there are many references to how these different types of wines will help the greater functioning of the internal organs as well as the temperament and mood of the drinker. There are frequent references to fever, gout, nausea, flatulence (both to reduce and increase, as needed by circumstance), poor eyesight, good gums, paralysis, tremours, poisoning, cancer, heart and brain afflictions, melancholy and good humour throughout. It is with reference to “Rosemary wine” (vino di rosmarino – p. 21) that Arnaldo uses the alchemical terms “L’acqua di vita” and “L’acqua ardente” (“Water of Life” “Burning Water) which is, of course, a stronger eau de vie concoction but also the alchemical mingling of opposites. The pharmacology of rosemary points to its long use for its antioxidant qualities (wine too!) and, in particular, to its salutary effects with respiratory disorders, inflammatory diseases, heart disease, cataracts, cancer and improved sperm motility. Also of note is also the encouragement of mixing various fruit (quince, for example) and plants and herbs (rhubarb comes up more than once). Furthermore, there are references to rosé wine (truly one of the oldest types of wine due to the technique of limited maceration that gives a pink, rather than red colour – favoured by ancient Greeks and Romans alike; here there is reference to rosewater) that is best for the summer. He writes, “Il vino estivo è propriamente un vino rosato” (27). There is mention of the technique of fining (the reduction of tannins in order to reduce astringency in red wines for early drinking) through the use of egg whites with reference to elder tree wine (vino di sambuco) and pomegranate wine (vino di melograno). In the brief section dedicated to vino di miele, or honey wine, there is also reference to the drying of white wine grapes that brings to mind vin de paille (straw wine) through the method of appassimento applied to white grapes. At the very end of the brief treatise there is praise for absinthe wine for its ability to act as an antidote against poisoning and can allow the healthy to visit with those afflicted of plague, so strong are its qualities. Considering that chronologically right around the corner is the Black Plague (1348), this is insightful advice. Perhaps the most revealing element of Arnaldo’s treatise is his reference to Vino d’oro (Gold wine, p. 22). He refers to gold as a mysterious, arcane perfect element containing properties in exact proportion that cannot be reproduced since it is a miracle of nature. Please note the insistence on NOT attempting to reproduce real gold. He writes that it “fosters improved vision, calms the heart and is the source of life, and cures leprosy” (23). He goes on to say the following: As you will have no doubt noticed, the height of the popularity of Arnaldo’s text appears from the end of the 15th century, through much of the 16th century. This coincides with the rise of a great number of recognized, famous Italian alchemists. This is also the height of the Italian voyages of discovery to the New World: Furthermore, this also happens to be the period of intense popularity for the Arcadia of Jacopo Sannazaro (1458-1530). This literary masterpiece, a pastoral work of prose and verse (prosimetrum), was composed in 1480 and published in Naples in 1504. Sixty-six editions of this best-selling work were published in Italy alone. Inspired by, for example, the works of Virgil, Theocratus and Boccaccio, to a degree, its recounting of an idealized pastoral existence had great influence beyond Italian literature. For example, in England, Sir Philip Sydney’s The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia of 1590 is one direct descendant as is the earlier Portuguese, Jorge de Montemayor's Los siete libros de la Diana, of 1559. Jacopo Sannazaro’s Arcadia also influenced the cartography of the New World for Giovanni da Verrazzano famously referred to the coastline north of Virginia as Arcadia with the result that the 1548 Gastaldi map indicates that famous reference with an explicit toponym. Here is where alchemy, Arnaldo da Villanova, Pope Clement V, Verrazzano, The Knights Templar, and Nova Scotia begin to converge in an intriguing Dan-Brownish sort of way: Arnaldo da Villanova, physician and alchemist dies mysteriously on a mission from Sicily to Avignon to visit Pope Clement V in 1311. This eminent figure famously produces the Papal Bull Clericis Laicos in 1306 to undo the work of his predecessor, Boniface VIII, whose Unam Sanctam asserted papal supremacy over secular rulers; on Friday 13, 1307 Clement V arrests the Knights Templar who were kind of holding the French King, Philip IV, hostage over debts incurred ever since the Crusades to the Holy Land and who charged them with usury, credit inflation, fraud, heresy, sodomy, immorality and abuses of all kinds. This resulted in their mock trials and mass burnings at the stake. This secret society went underground for centuries and all manner of mysteries (and blockbuster films, from Indiana Jones to James Bond series) have been attributed to them as a result. Some claim that their bones lie beneath Ca’ Dario, “il palazzo maledetto” (the cursed palace) that has led to the death and undoing of every one of its owners for centuries. Imagine how neurotic Woody Allen would have been if he had not discovered the curse and actually bought Ca’ Dario in the late 1990s! In The Lost Colony of the Templars: Giovanni Verrazzano’s Secret Mission to America, historian Steven Sora claims that Verrazzano had named the lands north of Virginia Arcadia because that was the name used by the Templars, and he had “found unmistakable evidence of the Templar presence in America but had located no colony.” These efforts would be taken up by the French and English nearly a century later. Only a few years after the Gastaldi map based on Verrazzano’s claims, Bolognini Zaltieri made an important modification: he famously referred to modern areas of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick as “L’Arcadia” in his 1566 Il disegno del discoperto de la nova Franza… . This toponym would later be transformed into the French “L’Acadie,” dropping the ‘r’ between the initial ‘A’ and ‘c’. Hence, the l’Acadie mentioned and indicated by France’s Samuel de Champlain and company have a direct link to Italian voyages of discovery and cartography. Samuel de Champlain's Ordre de bon temps (Order of Good Cheer – the oldest gastronomic and oenological society of the New World) founded 1606, also included Louis Hébert, the first Canadian apothecary, the equivalent of a modern pharmacist. He was also the first European farmer in Canada and planted the first grapevines near Port-Royal in 1611. Many modern histories refer to Louis Hébert as a direct descendant of the European alchemical tradition. When Samuel de Champlain and company arrived in the area, they also brought the first families with the surname Chiasson. Recent genealogical research has indicated that those Chiasson Acadians who arrived here as early as at least 1660 hail from the Italian-speaking Swiss canton town in Ticino, called Chiasso, near Lake Como. The Italian immigrant community of Nova Scotia can therefore claim its beginnings date back to the 1600s! Italians are, therefore, intertwined in Acadian history from the earliest days. They are part of that great effort of the Acadians to regulate the flooding of the Gaspereau Valley with those mysterious-looking dykes and turn it into the fertile valley that, ultimately, yields wonderful grapes that make such magical wine as L’Acadie blanc! The current alchemy of the wine industry is being produced right here in Nova Scotia with the efforts of the wineries throughout the province. Like the mysteries of medieval metallurgy, some of our wines are being unearthed like buried treasure and producing magical elixirs. Some local winemakers have tapped into these arcane secrets and are dropping not-so-subtle hints … . There is liquid gold and buried treasure in the alchemical wine being produced right under our very noses. If you haven’t tried them yet, tonight you get a small initiation … . Cheers! Works consulted: Alighieri, Dante. The Divine Comedy. Inferno. Trans. Charles S. Singleton. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1990. Carbonelli, Giovanni. Sulle fonti storiche della chimica e dell'alchimia in Italia. Lavis (TN): La finestra, 2003. Cavalli, Thom. Alchemical Psychology. New York: Tarcher/Penguin, 2002. Collins, Marsha S. Imagining Arcadia in Renaissance Romance. New York: Rutledge, 2016. Gilchrist, Cherry. Elements of Alchemy. Shaftesbury, Dorset: Element Books, 1991. Griffiths, Naomi E.S. The Contexts of Acadian History 1686-1784. Montréal: McGill-Queen's UP, 1992. Jung, Carl Gustav. Alchemical Studies. Trans. R.F.C. Hull. Princeton: Bollingen, 1983 [1967]. Maillet, Antonine. Rabelais et les traditions populaires en Acadie. Québec: Les presses de l'Université Laval, 1980. Peters, Moira & Craig Pinhey. The Wine Lover's Guide to Atlantic Canada. Halifax: Nimbus Publishing, 2016. Roy, Michel. L’Acadie, des origines à nos jours. Sherbrooke: Québec/Amérique, 1981. Sannazaro, Jacopo. Arcadia. Milan: Società tipografica de'Classici italiani, 1806. Sora, Steven. The Lost Colony of the Templars: Giovanni Verrazzano’s Secret Mission to America. Rochester, VT: Destiny Books, 2004. Villanova, Arnaldo da. Liber de vinis / Trattato sui vini. Manlio Della Serra, ed. Ciampino (Rome): Armillaria, 2015. Wood, Sean P. Wineries & Wine Country of Nova Scotia. Halifax: Nimbus Publishing, 2006. What follows is a series of screenshots from the Powerpoint presentation that listed the different wineries and their donations in alphabetical order. This presentation was projected onto an enormous screen at the front of the ICCANS hall during the tastings in order to offer a succinct profile of the wines that were being described by us, the pourers. The pouring progressed from the sparkling wines, to the whites, to the rosés, to the reds, from the lighter to the more fuller-bodied ones. Each slide would progress to the next at 30-second intervals. Once it ran through the entire cycle, the slide presentation would begin again in a continuous loop. This way, the 60+ guests were constantly surrounded by information about the excellent wines they were tasting ... without being overly intrusive ... . A big thank you (and SHOUT OUT!) to all the wonderful, generous people who helped make this such a fun and informative event complemented by fantastic wine! Cheers!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsAstrid Friedrich Archives

May 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed